My strategy engagements often start with interview feedback like the following:

- “We are doing too much.”

- “We need to focus.”

- “We need to decide what we AREN’T going to do.”

Leaders understand the need for trade‑offs. Or at least, the need for the focus those trade‑offs enable. Yet many leaders struggle to make these direction-setting calls — the ones that cut off one path in favor of another.

Strategic trade‑offs are the sacrifices leaders make to create sustainable and differentiated value for customers, relative to their competition. They are the discipline to say NO to “100 other good ideas” in support of saying YES to a very specific vision for the future.

Sounds straightforward — but it’s one of the harder acts of strategic leadership.

Obstacles to Making Strategic Trade‑Offs

Interestingly, we regularly and easily make trade‑offs in our daily lives. One of my personal trade‑offs is travel and adventure over, say, the latest technology gadget.

But in an organization, trade‑offs are where strategy and leadership meet. Those high‑stakes decisions impact everyone — from leaders to shareholders to employees and customers. Given the uncertainty of creating an unknowable future, it’s no surprise that so many leaders succumb to these common obstacles to making strategic trade‑offs.

1. Aversion to Limits and Constraints

Most leaders believe “more is better”—more customers, products, services. Anything less is “leaving money on the table.” It’s understandable. The expectation to consistently grow puts enormous pressure on business leaders.

Still, I would be hard‑pressed to find a leader who would disagree with the statement “We can’t be everything to everyone.” Trade-offs are required to create sustainable competitive advantage that delivers consistent growth. Strategic trade‑offs like the decisions by Southwest Airlines to use a direct‑flight model in contrast to the industry hub‑and‑spoke models, and to trade off meal service for advantages in cost and speed.

So why does saying NO to an opportunity or a way of creating value feel like a sign of weakness—a lack of creativity, ingenuity or capability? We perceive limits as negative. If someone tells me I can’t do something, I usually want to prove that I can (except cook, I am OK with that limit in my capability). Yet creativity is fostered by constraints, including creating a business positioned for the future.

2. Fear of Making the Wrong Call

Often our resistance to accepting limits is a protective mechanism based on the underlying fear of making the wrong call. The call to take one path at the expense of another — “Go North” or “Go South.”

Clearly, our endpoint can’t be North AND South. The choices are incompatible. We must choose a strategic direction, the proverbial fork in the road.

As the saying goes, “If you don’t know where you are going, then all roads will take you there.”

Directional decisions are needed to deliberately serve certain customers and needs in order to avoid sub-optimally serving the many. And with those decisions comes the hard truth that you will also make some customers unhappy—the ones you deliberately chose not to serve.

How do you feel when you read that? Did your stomach tighten? Mine did. What if you alienate the wrong customers? What if your choices don’t result in a financially viable business?

Rarely is a strategic leader asked to choose between a right and a wrong answer. Our job is not to get it right, but rather to increase the probability of success.

To manage this uncertainty, leaders may try to keep as many options open as possible, deferring the decision(s) until they “know more.” While this approach has a role to play in strategy and uncertainty, there are limits to its effectiveness.

When you defer those direction‑setting decisions for too long, you are left standing for everything. Which means you stand for nothing. Strategically adrift. At some point, you need to commit to cutting off one course of action in favor of another.

3. Focusing on Growth Opportunities Instead of Setting Strategic Direction

It is easy for leaders to fall into the “more is better” mindset when approaching trade‑offs as singular decisions. A strategy client had a long list of opportunities for their technology to be applied—oncology, multiple sclerosis, infectious disease. When I challenged the team to consider narrowing their focus, the challenge back was, “We will just get more resources so we can pursue them all.”

It is a common response, but a flawed mindset. We were not there to evaluate and fund different growth opportunities. We were there to set the strategic direction for the organization, a direction that would guide all subsequent decisions about what the organization would and would not do.

Our objective was to answer the question, “Who are you becoming?” An oncology company? A breakthrough research company? A technology platform? To do that, the team needed to make a cohesive set of trade‑off decisions, a set of choices that would result in an organization distinctly designed to deliver on its unique value equation.

It is that distinct set of trade-offs that is most difficult for competitors to copy. Competitors would have to completely change the way they design, manufacture, and ship furniture to compete with IKEA. Ironically, it’s what you choose not to do so you can do something else exceptionally well that creates advantage. Like Starbucks and McDonalds, who made a definite set of trade‑offs to create a unique strategic positioning.

4. Using Relative Trade‑Offs to Avoid High‑Stakes Trade‑Offs

Too many leaders fall into the trap of trading off a long list of individual growth opportunities instead of making the high‑stakes trade‑offs involved in setting their strategic direction.

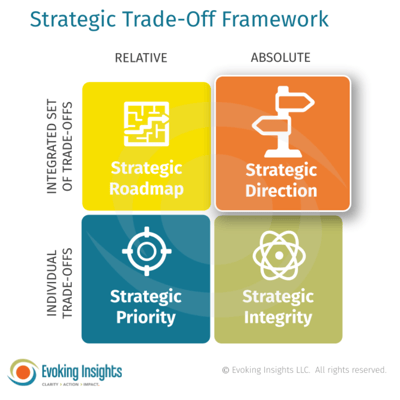

When you appreciate that trade‑offs are either absolute or relative, the reason why may become clearer. Take these two definitions as an example:

-

-

- Trade‑offs are the activities an organization chooses not to do (absolute).

- Trade‑offs are required when more of one thing necessitates less of another (relative).

-

The first informs what we “should” and shouldn’t do. The second is more contextual, informing relative priority over time or relative priority to each other.

You can appreciate that the first has more consequence to it. It is what some leaders call a “one‑way door” decision. By contrast, it is much more comfortable to make trade‑off decisions in the realm of the relative, the decisions that are fluid and can be adjusted as you go.

The strategic trade-off framework reveals this obscure, yet prominent dynamic. Leaders must avoid making individual trade‑offs without the benefit of the direction‑setting trade‑off decisions first. And they must avoid basing all trade‑off decisions on the resources available. It is a slippery slope that can prevent leaders from making the tough calls.

Absolute Trade-offs: Strategic Direction

When setting strategic direction, we make a set of absolute choices, what we will and won’t do. We stake a claim, making a bet on the best positioning of our organization for the future. Many other viable alternatives exist, AND we must pick just one to create a sustainable strategic position. These are high-stakes decisions, but not high frequency because they should guide the organization for years. No pressure!

Absolute Trade-offs: Strategic Integrity

Absolute trade‑off decisions also occur in the day‑to‑day. Without a clear direction, the basis for making day‑to‑day decisions is limited to financial analysis and advocacy. Without strategic clarity, it is hard, if not impossible, to say NO to compelling opportunities. Opportunities that would pass the financial hurdle. Opportunities your competitors may pursue. The only defining basis for the NO is in your most foundational and high‑stakes decision to “Go North.”

Relative Trade-offs

Most day‑to‑day trade‑offs are relative decisions—relative to each other, and relative to time. The question is no longer, “should we?” Instead, it’s “should we do this now?” Or, “how much of this should we do relative to that?” These are low‑stakes decisions, but they can become the riskiest of decisions for leaders who make all trade‑off decisions relative to avoid making those direction‑setting calls.

Next Time You Are Stuck and Avoiding Critical Trade‑Off Decisions

1. Accept

Limits are inevitable, and there are no right answers in strategy. So, what do you have? You and your team’s best judgment on the strategic position with the highest probability of success. Catch yourself when you or the team are avoiding critical trade‑off decision(s), or when you approach the trade‑offs as relative versus absolute calls. Be the voice that challenges indecision, and lean into the discomfort of making these direction-setting calls. This is strategic leadership in action. The quality of these strategic decisions is a function of a leader's capacity to:

-

-

- lead themselves and others through natural discomfort and fear in the face of uncertainty, and

- think strategically.

-

2. Clarify

-

Help to make those day‑to‑day trade‑offs by first clarifying your strategic direction. When your vision is clear, choosing those next‑level trade‑offs becomes clear. My math mind often thinks, “What are we solving for?” And in strategy, it is an advantaged position in the marketplace—creating distinct and superior value for our chosen customers and needs, relative to competition.

3. Explore

-

The options and alternatives to determine your strategic direction. Because whenever there are trade‑offs, there are equally viable alternatives. You will know your options are well framed when:

- a. There is meaningful trade‑off between the scenarios in terms of investment priorities, focus, and risk. Each option should provide a clear sense of opportunities to pursue or forego, leading to different outcomes and positioning in the marketplace.

- b. All options are attractive and viable. Anything less doesn’t force tough choices about where to focus your efforts and resources.

-

Trade‑offs are inevitable. We make them all the time, whether we realize it or not. To amplify your strategic impact, start with the absolute trade‑offs that define your strategic direction. I think of it like Russian nesting dolls. The outermost doll, in this metaphor your strategic direction, informs all subsequent decisions about what you will and won’t do. On this foundation, you can make much better day‑to‑day trade‑offs—positioning your business for the future.